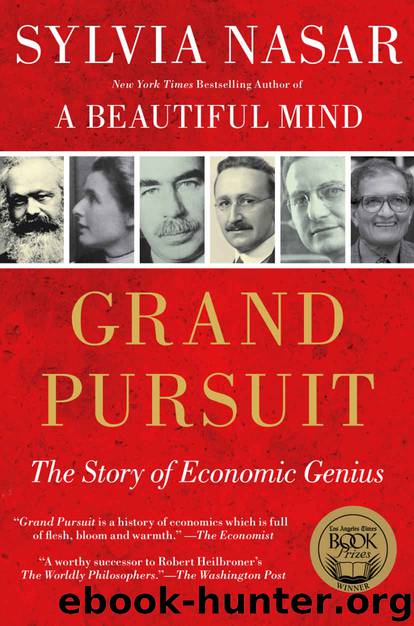

Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius by Sylvia Nasar

Author:Sylvia Nasar

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Published: 2011-09-12T14:00:00+00:00

Chapter IX

Immaterial Devices of the Mind: Keynes and Fisher in the 1920s

The world is gradually awakening to the fact of its own improvability. Political economy is no longer the dismal science.

—Irving Fisher, 19081

We should be led to control and reduce the so-called “business cycle.”

—Irving Fisher, 19252

The Great War had postponed the need for Keynes to settle on a career. At one time, he had thought he wanted to run a railroad, but railroads were no longer as glamorous as before the war. That high ground was now occupied by finance. The business of borrowing, lending, and insuring had been transformed by floating currencies, huge war debts, the urgent need for credit, and the vexing issue of reparations. Once a staid if mysterious backwater, finance had become the fastest-growing industry—or, in the eyes of skeptics, a giant casino.

Oswald “Foxy” Falk, a stockbroker friend whom Keynes had brought to the Treasury during the war, introduced him to the City, London’s Wall Street. Within a year Keynes found himself chairman of an insurance company. He knew nothing about insurance or the desirability of diversifying an investment portfolio. A life insurance company “ought to have only one investment and it should be changed every day,”3 he opined at his first board meeting. That Fisher’s notion of a trade-off between an investment’s risk and its rate of return had not occurred to Keynes is a sign of how novel it was. Like so many ideas that seem too obvious to require discovery, the idea that putting all one’s eggs into a single basket was risky was generally as little understood as Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Keynes by no means limited himself to running the insurance company. The collapse of the global gold standard, with its fixed exchange rates—something like a single world currency—during the war and its replacement by floating exchange rates had created a foreign exchange speculator’s paradise. When his speculation in francs, dollars, and pounds prospered, as in the fall of 1919 and the spring of 1920, Keynes was able to buy paintings by Seurat, Picasso, Matisse, Renoir, and Cézanne. “The affair is of course risky but Falk and I, seeing that our reputations depend on it, intend to exercise a good deal of caution,” Keynes assured his father, who, like several of his son’s Bloomsbury trust-fund friends, had blithely handed over several thousand pounds for him to manage. Perhaps the son’s next thought—“Win or lose this high stakes gambling amuses me”—should have set off warning bells.4

In this expansive frame of mind, Keynes took Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant on a whirlwind tour of the Continent in the spring of 1920. They paid a visit to the American art historian and promoter of Renaissance painters Bernard Berenson. At Berenson’s Florentine villa, I Tatti, Keynes and Grant each pretended, to their own but not their host’s great amusement, to be the other. But mostly they went shopping. Even Keynes, who tended to be a tightwad where trivial sums were concerned, bought seventeen pairs of leather gloves.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(108454)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12012)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8040)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7689)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7101)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(6600)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(6281)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6001)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5782)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4738)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4461)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4273)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4232)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4188)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4177)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3986)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3757)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3726)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(3571)